Vic Mensa sounds slightly disappointed when he gets on the phone. He’s at a random gas station somewhere in the middle of Florida, and all he wants is a decent cup of coffee and some healthy food. But that’s not going to happen. The Chicago rapper, who’s currently on tour in support of his Roc Nation debut The Autobiography, has one option—fast food.

The small sacrifices are worth it, though, and it’s safe to assume the intelligent, politically outspoken artist knows these are temporary first-world problems. The biracial 24-year-old grew up on the South Side of Chicago in one the most racially diverse and affluent (yet unpredictable) neighborhoods in the city—Hyde Park. Mensa’s experienced the complexities of the urban trenches, where crime, violence and poverty run rampant.

Throughout his musical catalog, which begins with 2010’s Straight Up EP, Mensa tackles topics that tend to fall into the dark abyss of tragedy, mental illness and drug abuse, something he explores further on The Autobiography.

On one of the album’s singles, “Rollin’ Like a Stoner,” Mensa raps, “Rollin’ like a stoner, I don’t care about everything / Out of control, I forgot to take my medicine / If I take this pill, will that be death of me? / I am a disaster, I don’t need a recipe / Tried to be sober, that didn’t work for me”—a glimpse into the inner struggles Mensa wrestles with on a consistent basis.

Like a lot of creative souls, Mensa has found that music always provides momentary periods of respite from the mental challenges that often accompany being an artist. High Times got to chop it up with Mensa about his fickle and complex relationship with drugs and why therapy in the hood is important.

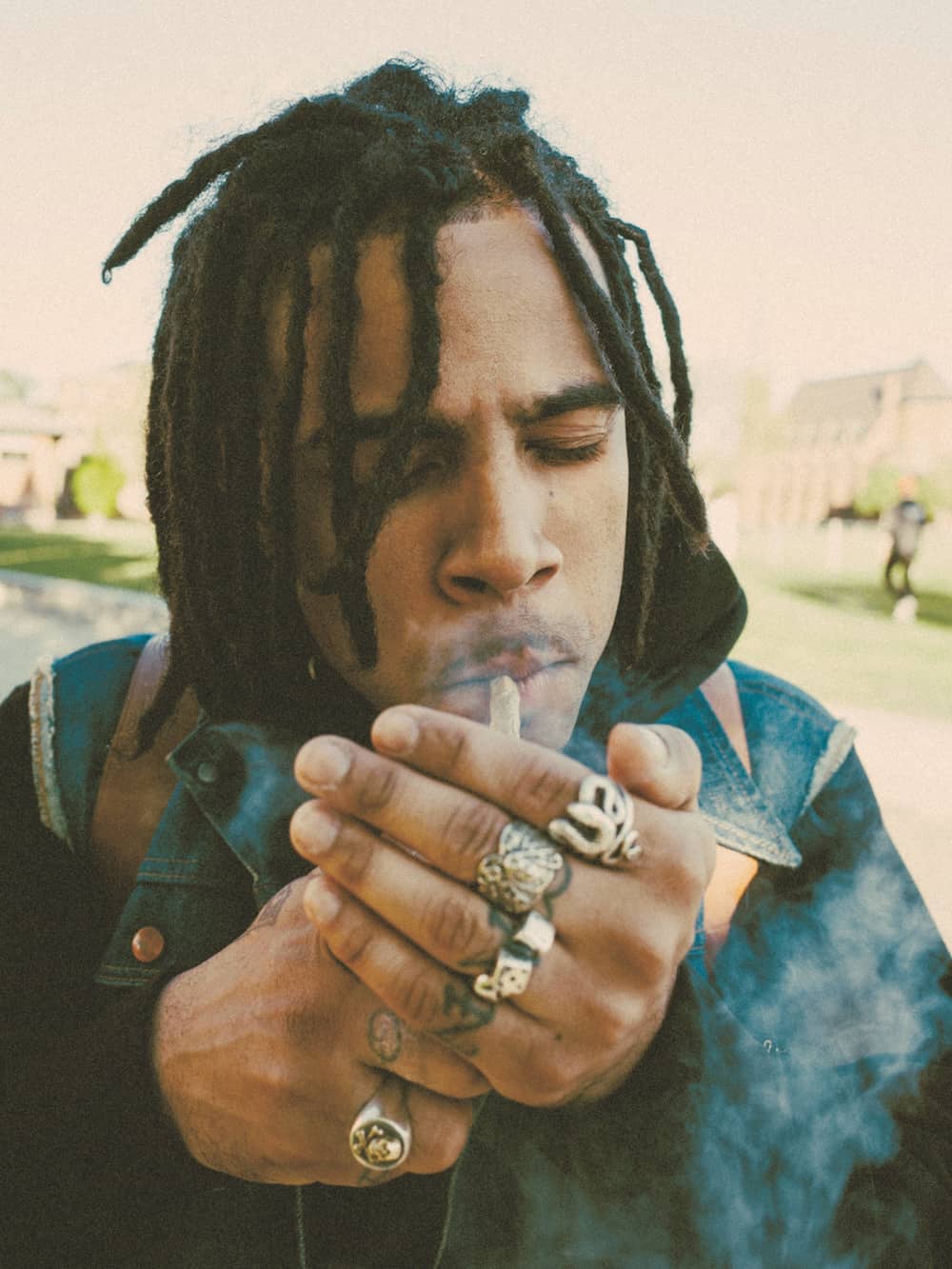

Jake Osmun

Hi, Vic. How are you doing?

I’m good. I’m on the road right now. I just jumped out of the bed—just now—and I’m about to get some iced coffee at Wendy’s. And I don’t even fuck with none of that type of shit. I’m not one of these guys, but I don’t have too many options, so…

I saw your recent interview with The Breakfast Club, and you had a Starbucks cup—

Yeah, I definitely fuck with coffee, but not like the fucking canned Starbucks shit out the gas station.

No, you need the real stuff.

I mean, there’s not options over here. This is what it is, though. I’m literally at a gas station connected to a Wendy’s.

I was curious about your relationship to drugs and alcohol right now. There’s a line in “Rollin’ Like a Stoner” where you say, “Tried to be sober, that didn’t work for me.” Is this something that you’ve been wrestling with for a long time?

Yeah, you know, I think that I kind of phase in and out. I really was writing that song about a point in time in my life, for the most part. I was fucking with a lot of drugs. I went sober and then I’d do hard drugs some time ago. But I still bounce back sometimes. It’s always something that I lean on—whether it’s weed or tobacco or alcohol or anything like that, so I took some pills and, you know, some harder drugs. I find that, very often, I could associate heavily with some type of external substance, but I’m working on that.

Do you think that more artists should speak honestly about drugs and alcohol rather than glamorizing it?

I think that’d be a good idea. I mean, considering how the nation is really grappling with this whole opioid situation. I do think that shedding some honest light on drug use is important. I also wanna say that in the media, we see manipulation is a powerful machine. I want to point out how much of a double standard it is that this opioid crisis is considered epidemic—when crack was wiping out black people in poor communities, there was a war on drugs.

Right, yeah.

Now it’s a medical crisis because it’s killing more white people. I just wanted to point that out, but I just think that regardless of the Ed Hammond race constructions, Americans, regardless of ethnic backgrounds, are dealing with addiction in a major way and having to adjust… And I wanted to address that honestly and candidly on my album. Because it’s a part of my life.

That’s essentially why you titled your new album The Autobiography, right? Because it’s very personal. In a recent interview you did, you were talking about how people don’t just wake up and go, “Everything’s great, let me take some Percocet and drink some lean” or whatever.

Right. Like there’s this sense of escapism.

So what do you think people are trying to escape from all the time?

Let me take a minute. I got to think about that right quick while I order these chicken tenders. [Laughs] I am thinking, though. Well, I would say that black people in Missouri and inner-city communities, their trauma is endless, and there’s a generational conflict. Black people carry the trauma of being ripped from Africa as slaves, and scientifically those anxieties are passed down through generations. I mean, you got a lot of people dealing with PTSD. Like I remember recently, Fredo Santana from Chicago opened up about his drug abuse, and he’s been having seizures and been hospitalized a lot recently. He had kidney failure or liver failure—one of those—from drinking so much lean and so much backwoods [blunts] all the time, and he was like, “Yo, I’m like trying to forget about all the things that I did and the things that happened to me in the streets.” He’s like, “I have PTSD.” A lot of people I know, virtually every one of my close friends, the vast majority of them, they all watched one of our friends be stabbed to death in front of them.

Wow.

A lot of people—I won’t say most—but a lot of people, a lot of youngins growing up in the hood, they witness death and despair firsthand. People’s mothers are strung out on crack, you know? Or people’s best friends. And we’re losing people to gun violence. We’ve all lost people—a lot of people—and we’re trying to deal with that trauma often through external substances. In addition to the fact that you got the pain of being made to feel less than by society. Black kids are suspended and expelled at a rate that’s astronomically higher than those of any other race in schools. You’re told from a young age that you’re bad and that you’re an issue. I mean, we’re watching people in the streets get shot down by police on a daily basis.

It seems like it’s totally out of control.

Okay, think about the need to kind of campaign what’s happening online right now with victims of sexual assault and sexual abuse.

Like with Harvey Weinstein? It’s crazy.

Women everywhere are being triggered by that, you know? I’ve spoken to a lot of women and people close to me that kind of have been pushed into the face of mental unwellness. They’re really being really triggered by this, just, wave of people coming forward about sexual assault. Imagine being—well, I don’t know what imagery you want, but imagine being a black person and watching Philando Castile bleed to death in that car next to his baby momma and a child, or watching Tamir Rice be shot.

Right.

Or watching Laquan McDonald be shot. These things are traumatic. Not only for the person being killed and the immediate families, but everybody that realizes that this could be me or this could’ve been someone I loved or maybe this has been someone I love, you know? The trauma is endless is what I’m trying to get at. Especially in the black community, addressing mental health is very taboo for a number of reasons.

One of the primary reasons being that there’s a classic archetype of a crazy black man or crazy black woman that has been used to divide and destroy black people. If you read Malcolm X’s autobiography, he tells the story of how after his father was killed by the Ku Klux Klan, the social workers ripped apart his family and stripped the children from his mother by labeling her as being crazy. She didn’t want them to… or she didn’t have them eat pork, so even though they were poor, they were rejecting pork, which the social workers jumped on to say, “She’s crazy.” And one by one, they stripped the kids from her and she ended up in a mental asylum.

Right. So, because she was struggling financially and refused free food, they thought she was nuts.

Exactly. So we have these classic categorizations that have been used to demean and dehumanize you, like it’s understandable that black people stay away from addressing mental health because nobody wants to be in that box.

It’s starting to change, though. I think that stigma is starting to lift, and I’ve been really encouraged by that too.

I think so too, yeah.

You’ve addressed depression and things like that in some of your interviews, and it’s so important. A lot of fans out there routinely elevate these artists to the status of superhuman, and so when you come down to this vulnerable level, it really helps. It spreads awareness and gets the message out there that it’s okay to admit you have a problem.

Yeah, I 100 percent think that the stigma is lessening, but it still needs to be introduced in a major way. You know what I’m saying? We doing Wall Street, and everybody and their family of CEOs sees a therapist. Everybody down to the dog, you know? But I don’t know one—not a family, not an individual—not one lady from the hood that sees a therapist.

Damn. I think I see one every week.

I talk to my therapist all the time. But I think this is something that people need to understand. This shit’s not free right there. It’s not in school. There aren’t therapists in public high schools in the inner city of Chicago. I mean, there’s not even music teachers.

That’s crazy.

There’s not even a traveling therapist in a school once a week. It’s like there’s not one person in the hood that’s seeing that. It’s not an affordable thing. So I think that addressing mental health should be something that should be subsidized and a part of health care. I think all that shit should be free for Americans, especially when they’re seeing how people are escaping through these drugs and destroying their lives.

Jake Osmun

I also wanted to get your comments on fellow rapper Meek Mill and his recent two-to-four-year prison sentence. The sentence that he got is so insane, and I wanted to get your thoughts on why you think the judge decided to give him such a stiff punishment for probation violations.

The powers that be want Meek Mill to be a slave of the state. Point blank, period. Let’s not forget that a fat cat in a tall building gets paid off of every inmate in many situations. There are still privatized prisons all over this country. There is prison labor being used to produce everything from Starbucks cups to pens and pencils, you know what I mean? It’s slave labor, you know what I’m saying? And they want Meek Mill as a ward of the state, and what’s even more convoluted about it is that the judge is a black woman. But it’s not new. That’s a common function of neocolonialism. The colonized and the oppressed will begin to identify with the oppressors. That’s just classic Stockholm-syndrome-type shit, but it is twisted.

They should appeal the conviction and reconsider because it doesn’t make any sense.

Yeah, they’ll definitely appeal.

I wanted to just touch on your taste in music. You started listening to, like, Prince and Nirvana and rock early on, and then kind of got into hip-hop later?

Yeah, exactly.

And then you got to fill in for Del the Funky Homosapien when performing with Gorillaz. What was that moment like, stepping into that role?

Oh, with the Gorillaz? Yeah, I love the Gorillaz. I think the Gorillaz are one of the best examples of the hip-hop genre bending pop, going major. That was amazing. Damon [Albarn] is a genius.

Was it intimidating working with him at all?

No, he’s really cool. After getting to know him, he’s interesting.

He’s really welcoming of the younger generations. I think it’s really awesome that he’s kind of open to working with all types of different MCs and stuff.

Yeah, me too. That’s cool.

This feature has been published in High Times’ magazine, subscribe right here.

The post The High Times Interview: Vic Mensa appeared first on High Times.

0 DL LiNKS:

Post a Comment

Add yours...